Introduction to the manifestation of

Indonesian wooden Architecture

"International Conference : Manifestation of Architecture in Indonesia"

Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, Surabaya 2015

see Japanese text "インドネシア木造建築研究序説"

see Japanese text "インドネシア木造建築研究序説"

Prologue

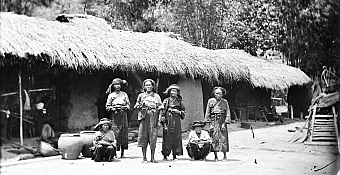

It was in 1985 that I first visited Indonesia.

I became interested in Indonesian wooden architecture through architectural magazine published in Japan during the Second World War showing various forms of wooden architecture in the frontispiece.

In Japan, there are many wooden buildings existing for more than 1000 years, which developed concrete systems to maintain such cultural asset and their carpentry skills as well. It seemed to me Indonesian architecture goes a different direction from our common knowledge about wooden architecture; by geographical location or ethnic group, its treatments are diverse and unique like zoological / amusement park.

“How have a series of Indonesian architecture been developed? ”

“What is the concept?”

I was very much impressed, or even shocked by its uniqueness differed from one region to another, or one ethnic group to another. -this is the beginning of my long long journey to Indonesia.

At that time, we have extremely-limited information about Indonesian wooden architecture. Even in Indonesia, architectural students devoted themselves to modern architecture and have less interest to their own culture exept famous historical monument like Candi Borobudur.

“Kompendium: Sejarah Arsitektur” (1978) was the only general information manual on history of Indonesian architecture. Its author, Djauhari Sumintardja, was working as a researcher for "Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Permukiman" (Research and Development Center of Settlements) that is affiliated with "PU" (Ministry of Public Works), reporting regularly for a bulletin called “Masalah Bangunan” (Building Problem) about traditional houses and its characteristics in different ethnic groups. (*2)

On the one hand, "PdK" (Ministry of Education and Culture) has also started to build documentation of traditional houses as a part of "Proyek Inventarisasi dan Pembinaan Nilai-Nilai Budaya" (Project of the Inventorization and Management of Cultural Value). Unfortunately, they could not achieve concrete results to answer architectural questions, but 40 years after the independence, they completed a report on patterns and styles of traditional houses by state. (*3)

From a global perspective, studying the traditional houses in Indonesia has become significant field for anthropologists; they often appeared in discussion on symbolism, for example, “Order in the Atoni House” written by Clark Cunningham in 1964, “RIGHT AND LEFT: ESSAYS ON DUAL SYMBOLIC CLASSIFICATION” that includes Cunningham’s essay edited by Rodney Needham in 1973, and “THE FLOW OF LIFE: ESSAYS ON EASTERN INDONESIA” (1980) edited by James J.Fox. (*4)

By contrast, in the discipline of architecture, Gaudenz Domenig discussed in “TEKTONIK IM PRIMITIVEN DACHBAU” (1980) about architectural culture of Austronesian including Indonesia, and Japan during prehistoric period. His theories generated a great deal of interest in Indonesian architecture among Japanese architects including me. (*5)

Maybe should mention that “THE HOUSE IN SOUTH-EAST ASIA” (1987) by Jacques Dumarcay and “THE LIVING HOUSE: AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF ARCHITECTURE IN SOUTH-EAST ASIA” (1989) by Roxana Waterson have not appeared at this stage. (*6)

I arrived at former Halim international airport in Jakarta for the first time with the above-mentioned premise.

Now, I have prepared two topics about Indonesian wooden architecture;

Firstly, I would like to introduce my hypothesis to understand the history of Indonesian wooden architecture and its diversity.

Secondly, I will discuss about two crisis cultural properties of Indonesian architecture are facing.

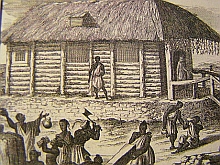

from September 1942 issue of “the Journal of Architecture and Building Science”(*1)

Biggest house of Karo Batak in Kabandjahe. more than 100 inhabitants reside in its 20 rooms

Adat house "Museum Minangkabau" in Padang pandjang

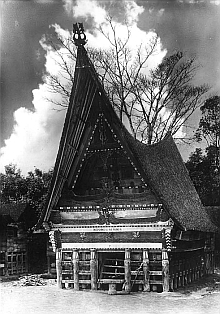

Toba Batak House

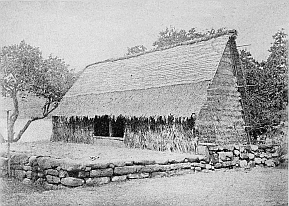

Granary in Northern Bali

1. Brief History of Indonesian Wooden Architecture

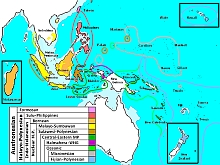

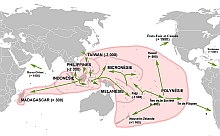

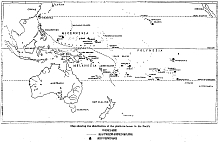

To get start with my hypothesis, I have to mention Austronesian architecture. Austronesian languages is dispersed throughout Polynesia, Micronesia, Melanesia, Indonesia, Philippines and part of mainland southeast Asia, which has been stretched from Easter island in the east to Madagascar in the west, and from Hawaii in the north to New Zealand in the south. Japan is considered to be different language and ethnic group, but historically can be considered to be existed within the same cultural area.

In Polynesia, houses are called as "fare", and the term "fare" is used in Philippines. In Indonesia, public buildings are often called as "bale". On the one hand, houses are called as "imu" in Micronesia; this can be linked with "rumah" in Malay, which is called as "uma" in Sumba island, "amu" in Savu island, and "omo" in Nias island. People living in these areas appears to be the same language group.

It is assumed that Austronesian language family began to migrate about 5000 years ago. According to archaeological and glottochronological studies, Taiwan is believed to be its starting point. (*7)

Although the truth always seems to be suspicious, it is necessary to point out three key issues in regard to Austronesian architecture;

First, what kind of buildings had they brought with when migrating about 5000 years ago?

Second, how has raised-floor house that are currently seen in Indonesia been expanded throughout the area?

Third, what kind of houses had they lived in before the emergence of raised-floor house?

To answer the first question, they in fact did not have raised-floor house with them when starting migration. So that means the second question will be “how has raised-floor house been brought to this area? ”, and if so the third question will be “what kind of houses had they lived in before the arrival of Austronesian peoples?”

1-1. Austronesian Architecture

What kind of buildings had been existed when Austronesian people got started migration?

In general, raised-floor houses cannot be seen in Polynesia and Micronesia although there is an exception including Palau; instead the whole structure is built on stone-masonry platform. In Taiwan that is supposed to be the starting point of Austronesian peoples, most indigenous people utilize stone-masonry for floor as well as for wall of houses with earthen floor.

This is the diagram of a house in Marquesas islands that is located in far east of Polynesia explaining that two main ridge-posts stood at the both edges of house support a ridgepole, on which rafters are directly leaned from the ground to make a roof-construction without wall; walls are installed only in the entrance side of the house, but it does not have a floor structure.

The house building structure in Yap island in Micronesia is more easy to understand; it is the same as the example in Marquesas that ridge-posts support a ridgepole, but every horizontal members of building are supported by individual posts placed directly in the earth. The role of each post is very simple because there had not been an idea of establishing rigid framework on the foundation stone. The houses have seemingly huge boat-shaped roof, which may have been influenced by Đông Sơn culture. Instead of raised-floor structure, it had been constructed on the masonry platform.

I believe that Austronesian people had brought houses based on such structural concepts with them when they first started their migration.

1-2. Expansion of Raised-Floor House

How have the raised-floor houses been constructed that can be currently observed throughout Indonesia? (*15)

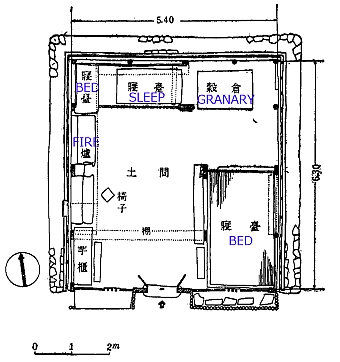

For example, an ethnic group called Bontoc in Luzon inhabit earthen floor instead of raised-floor. When entered through the entrance, rice pounding room and fireplace are located on the right and a bench is installed on the left. There is a small room at the end surrounded by walls and used as bedroom, in which grass is spread over the ground and they are directly sleeping on it. Next to the bedroom, there is a large chest made by combining different pieces of boards, which stores harvested rice. Bontoc house is quite similar to that of the indigenous people of Taiwan in terms of its spatial arrangement.

It is interesting that their house, “fare” is derived from raised-floor construction although they have made their livings on the ground. There is a granary-like structure supported by four posts in the centre of the house; such structure has appeared in constructing process of the house. They do not use granary-like structure for storing rice crops, but the male owner get up on the raised floor and light a hearth there to practice cock sacrifice after harvesting rice.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Maligcong, Mountain Province, Luzon, Philippines

Ifugao is a neighbour group of Bontoc, who are famous for their terraced rice fields that were registered as a World Heritage site. They diverted raised granary that is located in the centre of Bontoc house into their residencial house called “bale”. It can be assumed that raised-floor were introduced with wet-rice cultivation into this area and they used its rice granary for dwelling, which can be related to the fact that this kind of raised-floor houses did not exist among the indigenous people of Taiwan who had not engaged in wet-rice cultivation until 19th century.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Banaue, Ifugao Province, Luzon, Philippines

In contrast, it is interesting to see that Bontoc people have still lived under the raised-floor, which shows the process that raised-floor house had been transmitting. This kind of examples can be also seen in Indonesia.

granary-like Ifugao house, Luzon (1982)

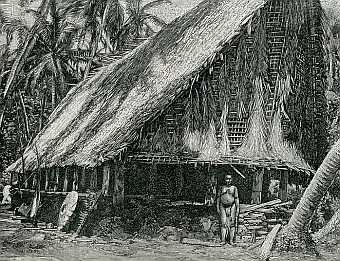

In Leti islands located in southeast Moluccas, people also live on the ground (under the raised-floor) of their house called “rumeh”, in which raised-floor style structure are applied. By piling up timbers alternately in ridge or span direction, they make raised-floor structure of parallel crosses style, which are also common to Bontoc.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Desa Tutukey,Kec. Pulau-Pulau Letimoa Lakor, Kab. Maluku Tenggara Barat, Maluku, Indonesia (1986)

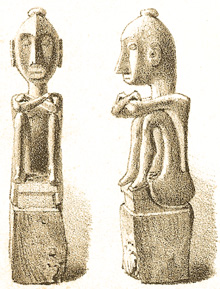

Attic space is not used for daily life, but for rituals including wedding and funeral. For instance, when one dies, a small wood carving figure “yene” that symbolizes the deceased will be made and placed on a shelf installed on the gable roof side. Such ancestral figures in Leti that are squatting down are broadly seen among the Austronesian as well as in Ifugao in the island of Luzon. In Ifugao, ancestral figures represent a guardian of rice named “bulol”. After harvesting rice, people perform the granary-rite in order to activate bulol idols. The idols are doused with rice wine and their faces are smeared with rice cakes.

When I conducted an investigation in 1986, several such traditional houses still have been remained in Leti. Tracing the modification of house structure in Leti, we can recognise a brief history of raised-floor, which in the beginning combinates timbers in sophisticated manner, going through simplification process comes to be an ordinary attic in the end. If we look at only this last stage it is impossible to know that the house construction of Leti is originated from raised-floor granary. A clue to trace the history within wooden architecture is missing forever.

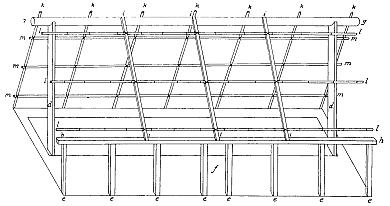

1. original raised-floor structure

sophisticated timber combination

2. omit support posts and beams

ridge-post divided into post and kingpost

3. omit ridge-post

4. raised-floor become ordinary attic

Familiar examples can be also seen in Bali. It is well-known that Balinese cosmology is based on relative orientation between kaja (mountain direction) and kelod (sea direction) that centres around the holy mountain called “Gunung Agung”. It is believed that kaja represents life whereas kelod represents death; therefore, settlements and houses are always located according to kaja - kelod directions.

communal granary jineng, Tenganan, Bali

bale tengah - entrance to attic from outside

Balinese indigenous people known as “Bali Aga” in Tenganan also follow such cardinal direction. There is a communal rice storage jineng on a public street that runs at the centre of the village. So, what do you think how do individuals keep their own rice grains?

As is the case with Balinese house, several types of building are laid out in the compound of Tenganan house; the main building is called “bale tengah”, in which people perform rituals, and its attic space is used for rice storage. In other words, it can be said that they are living under the rice granary.

2012KojiSato.gif)

"Bale Buga (house for ritual), Bale Tengah (house for initiation), Meten (bed room), Paon (kitchen)"

Tenganan, Kec. Manggis, Kab. Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia (1985)

It is known that Sasak people in Lombok also exceptionally do not live in raised-floor house. They instead build their house bale on earthen platform.

2012KojiSato.gif)

However, people in Bayan region located in the northeast of Lombok island also utilize earthen floor for living, but have raised-floor structure “inan bale” (center of bale) in their house. Though ritualistic meaning of this raised-floor space was displaced by Islamization, this architectural remain still suggests the origine of Sasak house.

inside Sasak house “dalam bale”, Sembalun

raised-floor remain “inan bale”,Bayan

The easiest way to utilize raised granary is to live in its rice granary itself. There is another example in Indonesia, which is similar to Ifugao in Luzon. In Sumbawa island, there is an ethnic group called Donggo, whose houses “uma” have wooden disks for rat-guard on the top of four main posts that supports the raised-floor, which reveals that it was originally a rice granary; it still remains in the inner part of living space.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Sangari, Desa Mbawa, Kec. Donggo, Kab. Bima, NTB (1985, 1986)

Now, I will introduce some examples to look at how raised granary has developed into various kinds of raised-floor architectures.

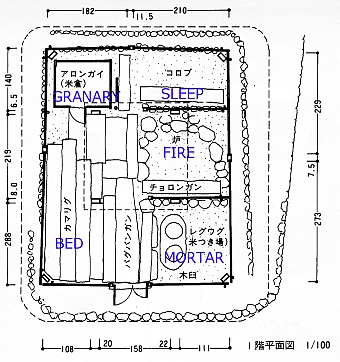

“Fala” is a house seen in Alor island and similar to Donggo, which is derivative of raised granary located on the top of four main posts. In Alor island, raised terrace is usually equipped under the raised granary, in which men spend most of time. The terrace has a hearth for men, but the main cooking hearth is placed inside of the raised granary that is used as residential space for women and children. Sacred utensils including bronze drum well-known as “moko” in Alor are also stored in the attic of raised granary.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Takpala, Desa Lembur Barat, Kec. Alor Tengah Utara, Kab.Alor, NTT (2013)

A pattern of raised-floor houses that has developed from opened terrace installed under raised granary can be also seen in Sumba island.

Sumbanese house “uma” is well-known for its unique peaked roof, in which ancestral spirit called “marapu” is enshrined and heirlooms handed down from their ancestors are placed. There are four posts supporting the peaked roof, which is believed to be sacred among them. In western district of Sumba island, a rat-guard is always equipped on the top of these posts, which suggests an attic structure of the house has been originated from raised granary; it means their living space located under the attic derived from raised terrace.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Desa Wunga, Kec.Hahar, Kab.Sumba Timur, NTT (1987)

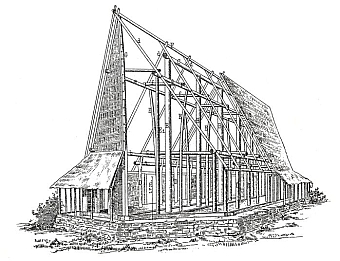

These similarities can be observed in totally different styles of house - for instance, it can be understood from its building structure that a huge boat shaped house called “ruma” of Toba Batak people in Sumatra has been developed from terrace installed on raised granary “sopo”.

2012KojiSato.gif)

2012KojiSato.gif)

Finally, I will show an example of Javanese house “omah”.

At present Javanese houses do not have raised-floor structure, but have a symbolic form, combined of “pendopo” that is an opened hall with no walls and “dalem” that is a main building located behind pendopo. Pendopo has a peaked roof supported by four sacred posts, “soko guru”. Similarly, dalem has a space supported by four posts, and in the innermost part three rooms are partitioned; the central room called “krobongan” houses rice goddess “Dewi Sri”, to whom daily offerings are made by the mistress of a house. This room is taken up by ritual equipments such as a decorated bed, on which a large number of cushions are piled up. On the evening of the wedding day, the bride and bridegroom sit for some time in front of the krobongan.

It is said that dalem is a private space for a family that represents female character, on the other hand, pendopo is a public space for men, where the head of a family receives his male guests and performs ceremonies for ancestral spirits.

masculine and public pendopo

faminine and private dalem

formal decoration of krobongan (National Museum of Indonesia, 1990s exhibition)

Considering the significance of the two contrast of Javanese house, krobongan is analogous to granary itself characterised by the faminine and private activities, whereas pendopo is rather analogous to the space under granary characterised by the masculine and public activities. Therefor it will not be unreasonable that Javanese house is originated from raised granary which had been divided into two parts; its upper part slid in parallel direction to become krobongan whereas the under part remained as pendopo. At that moment gender separation had completed symbolically in Javanese house.

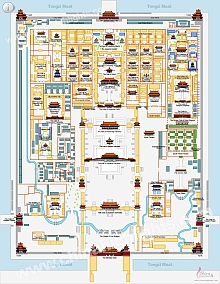

In general, raised-floor architecture is analyzed vertically into three levels of space division such as substructure / mainstructure / superstructure, that is corresponding to the symbolic tripartition of the cosmos, namely underworld / humanworld / upperworld. But in Javanese house spatial symbolism seems to be based upon horizontal direction instead of vertical direction. The same handling of spatial symbolism is very common in Chinese architecture, where the rank of space is getting higher and higher when going through inner area. This may suggest that the transformation of Javanese house had occured by the Chinese influence.

2012KojiSato.gif)

vertical symbolism: sacred house among Ngaju Dayak imagined between underworld symbol "naga" and upperworld symbol "hornbill"(*18)

horizontal symbolism: Forbidden city, China

Raised granary has been also brought to Japan. In Nansei Islnads, it has been used until recently.

Amami Oshima (1999)

Yoron (1999)

Okinoerabu (1999)

Okinawa (1999)

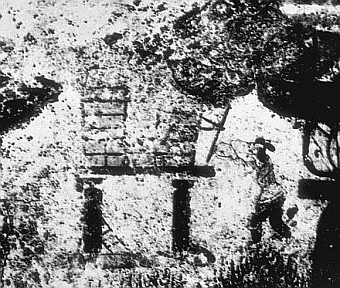

On the one hand, raised granary of parallel crosses style is dipicted on the “Decoration of Frontispiece Paintings of Sutras in Gold Lettering in the Collection of Chuson-ji Temple” in 12th century, and on the other hand, raised granary with similar structure can be observed in mural of Koguryo tumulus painted during “Koguryo” period from 4th to 5th centuries in Korean Peninsula.

frontispiece paintings of Sutras, Chuson-ji c.12C

mural of Koguryo tumulus 4-5C

This kind of architectural form may have been expanded further to the northern district; needless to say, it resulted from the spread of wet-rice cultivation. Although it is unknown when wet-rice cultivation was started in Indonesia, it is said that it was introduced to Japan about B.C. 3C at the beginning of “Yayoi” period when raised granary firstly appeared (recent excavation have shown that rice cultivation had begun 700 years earlier). It seems there is not a big gap in the beginning period of rice cultivation between Indonesia and Japan.

1-3. Boat Symbolism

Boat-shaped roof characterizing the Indonesian wooden architecture has its backgroud in the following folk belief.

Ancesters sailed by boat from the westward where their imaginary homeland is located, and then the spirits of the dead should be launched by a spirit-boat again toward the westward/downstream back to his homeland.

In this sense house is analogous to ancester's boat and coffin is thought to be a boat of the dead for returning home.

Houses with boat-shaped roof are depicted on the cowrie-shell container and the bronze kettle drum excavated in the mainland, which going back to the several centuries B.C.

modelled house on cowrie-shell container

BC2-1C (Shih-Chai Shan, Yunnan)

boat-shaped house depicted on Đông Sơn drum

BC3C? (Hoàng Ha, Vietnum)

It is obvious that these archaeological findings gave a clue to understand the origine of boat motifs expressed in Indonesian houses; a group of ancester sailed from their homeland, that is Vietnam or South China, had brought the bronze age civilization together with boat-shaped house to Indonesia !? (*19)

Makalamau drum from Sanggeang Island near Sumbawa

c.3C? (*20) (National Museum of Indonesia, Jakarta)

We come across similar house style as depicted on the timpanum of Đông Sơn drum among Toraja people of Sulawesi island. Toraja is well-known for its scenic village where two rows of ancestral houses “tongkonan” and granaries “alang” are layed out in parallel. As is usually the case with Austronesian, Toraja don't have the idea (word) of north / south direction, but instead, they follow the axis of upstream / downstream for planning their villages. Tongkonan, as the legendary vehicle of the ancester who ascended a river to Toraja-land, faces toward upstream, the direction of front/future/life symbolically, on the other hand, alang faces toward downstream, that of back/past/death. This is the reason why alang is associated with death during funeral celemony.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Sa'dan Sangkombong, Kec. Sa'dan, Sulawesi Selatan (1991)

houses (left) toward upstream whereas granaries (right) downstream, Ketekesu (2005)

トラジャ(スラウェシ島) | Toraja (Sulawesi)

トラジャ(スラウェシ島) | Toraja (Sulawesi)

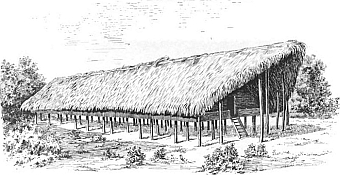

Along with Toraja, Batak Toba in Sumatra is also famous for its splendid architecture with boat-shaped roof. Similar to Toraja, villages of Batak Toba consist of parallel rows of houses “ruma” and granaries “sopo”.

Though the association with the boat culture is not clear, other examples with the same attitude to the roof design can be found out in many places of Sumatra like Pasemah / Besemah, Manangkabau, Aceh and so on.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Limo Kaum, Batusangkar, Sumatra Barat (1990/2011)

Minangkabau house “rumah gadang” with projected wing “anjung”, West Sumatra (2011)

ミナンカバウ | Minangkabau

ミナンカバウ | Minangkabau

2012KojiSato.gif)

Indrapuri, Kec. Indrapuri, Kab.Aceh Besar, Aceh, (1990)

However, it is in the eastern part of Indonesia where the concept of boat symbolism is most widely manifested.

Savunese house “ammu” is said to be a boat overthrown directing its ridge toward east/west; men's entrance opens in the bow-side whereas women's in the stern-side. The stern half serves as women's domain, above which women's loft is equipped. Only the wife of the househead is allowed to enter the loft.

After the harvest, each house make a small leaf container filled with harvested sorghum and set to sea in the direction of the other world, where the soul of the dead will sail to and the first ancestor of Savu came from. At the same time, housewives place offerings of sorgham at the base of the women's post in the loft.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Desa Limaggu, Kec. Savu Timur, Kab. Kupang, NTT (1987)

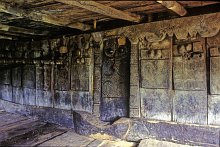

Bunaq people, residents of the mountain region in the East Timor border, utilize raised-floor house “deu” decorated with elaborate carvings of breast and labyrinth on the facade wall. Deu is compared to a boat supported by two main ridge posts, that is, masculine “nulal lor” (post of sea) in front and feminine “nulal hoto” (post of fire) behind.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Desa Ekin, Kec.Lamaknen, Kab.Belu, NTT (1987)

breast and labyrinth: wooden reliefs on the entrance wall of Bunaq house “deu hoto” (1987)

ブナッ(ティモール島) | Bunak / Bunaq (Timor)

ブナッ(ティモール島) | Bunak / Bunaq (Timor)

Boat symbolism is also pointed out among Lionese house “Sao” in Flores island or Rotinese house “Uma”.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Koanara, Kec. Wolowaru (Kelimutu), Kab. Ende, NTT (1986)

ridge post “mangu” (mast) support ridgepole where ancestral deity dwell, Lio - Flores Island (1986)

リオ(フローレス島) | Lio (Flores)

リオ(フローレス島) | Lio (Flores)

2012KojiSato.gif)

Sunsa, Kec. Rote Barat Daya, Kab. Rote Ndao, NTT (1987)

In Japan boat-shaped roof suddenly appeared among archaeological findings dated back to Tumulus Period; clay images of house, which were buried with the dead, are mostly characterised by its exaggeratingly overhanged gable end. The same roof style is expressed in the four different buildings depicted on the famous bronze mirror “Kaoku Monkyo”. The appearance of boat-shaped roof in Japan is supposed to be between the 3rd to 6th century.

Clay Image of House 5C

(Saitobaru Tumuli, Miyazaki)

Bronze Mirror 4C

(Samida Takarazuka Tumuli, Nara)

Bell-shaped Bronze

BC2C (Kagawa)

Considering the raised floor building depicted on the bell‐shaped bronze vessel from Kagawa, the start of boat-shaped roof can go back to BC 2C, however after several centuries of enthusiasm, Japanese architecture payed no attention to boat-shaped roof any more. Judging from the diffusion of Đông Sơn culture, boat-shaped roof supposed to be introduced in Indonesia at the same period as in Japan.

1-4. Pre-Austronesian Architecture

Now we proceed to the final question; before the Austronesian expansion over Indonesia what kind of architecture had indigenous people utilized ?

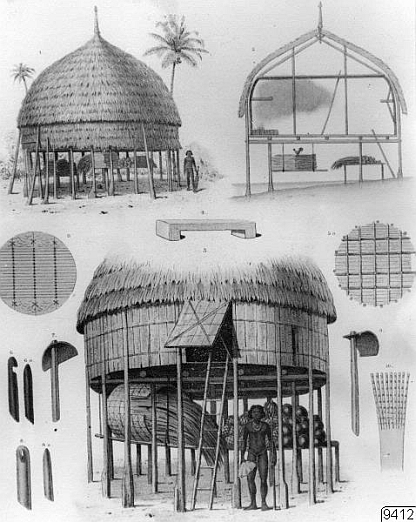

When looking over this whole area, it is suggestive that houses with round plan still remained both in New Guinea of the extreme east and in the Andaman and Nicobar islands of the extreme west. Pre-austronesian architecture of this kind was also found in the Enggano island on the west coast of Sumatra where indigenous people dwelt in the elevated house like a bird's nest named “yuba kakadie” (round house) until the beggining of 20th century.

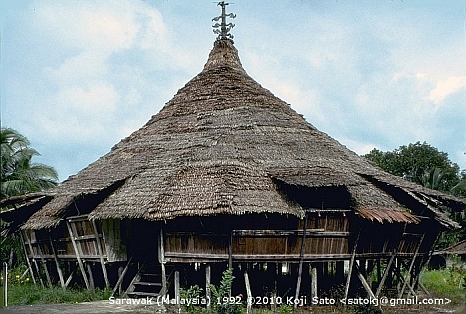

As is often the case with Austronesian, there is a communal house with special function for the social activities in a village besides ordinary dwelling houses. As housing space belongs to women's domain in general, the communal house of this kind comes to be a lodge for unmarried men and serves as a place for village meetings or ceremonies after harvesting, headhunting etc. In Borneo where villagers commonly use a longhouse for living, Bidayuh people also build a round men's house “Bori Baruk” for storing spoils of human skulls. (*24)

head house Bori Baruk among Bidayuh

Sarawak-Malaysia (1992)

inside Bori Baruk

human skulls are enshrined

2012KojiSato.gif)

Opar, Bau District, Kuching Division, Sarawak, Malaysia (1992)

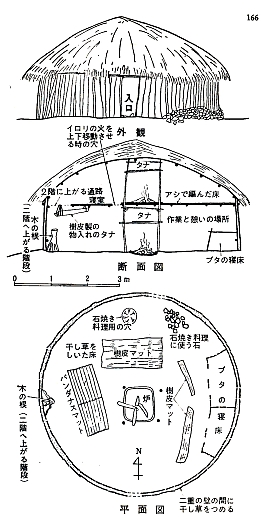

Atoni people of Timor island use a round earthen-floor shed “ume” for the dwelling of a nuclear family. Originally only a chief can possess a raised granary “lopo” with tall roof of beehive shape. Lopo is actually a public building erected on high stone platform, where village meetings are occasionally held. The whole structure of ume is supported by four main posts; the idea of which presumably was borrowed from the structure of lopo as we already saw many examples in other places of Indonesia. In Atoni village there is also a sacred house “ume leu”; the external appearance is similer to that of ume but its structure is different; i.e. not four posts but one central post supports whole construction. This central sacred post is erected on stone platform and adorned with various sacred heirlooms handed down from ancestors. It is supposed that former traditional architecture was remained as a sacred house when they had accepted the innovative construction of raised granary.

Atoni sacred house ume leu

Timor Tengah Utara, NTT (1987)

Atoni Granary lopo

Timor Tengah Selatan, NTT (1987)

2012KojiSato.gif)

Kefamenanu Selatan, Miomaffo Timur, TTU, NTT (1987)

2012KojiSato.gif)

Oeleu, Amanuban Tengah, TTS, NTT (1987)

round house and raised granary among Atoni people, Timor (1987)

アトニ/ダワン(ティモール島) | Atoni / Dawan (Timor)

アトニ/ダワン(ティモール島) | Atoni / Dawan (Timor)

Also in Timor island Bunaq house “deu” as described above might derive its oval form from ancient round-house; moreover elevated round-house “mbaru” of Manggarai people in Western Flores and raised-floor house with oval plan “omo” in north Nias can be considered as the same tradition.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Waerebo, Kec. Satar Mese, Kab. Manggarai, NTT (1986)

2012KojiSato.gif)

Helefanikha, Kec. Gidö, Kab. Nias (1990)

Besides round-house, longhouse, a kind of today's apartment house, is supposed to be one of the oldest house style in this area, especially among the people living in mountain regions of mainland southeast Asia and in Borneo where various ethnic groups are scattered like a mosaic because powerful royal authorities were undeveloped. (*26)

Ethnic minorities of both Austronesian and Austroasian/Mon-Khmer people of highland Vietnam still use longhouses for their daily life; in addition to longhouse they usually build a communal man's house Nhà Rông characterised by its huge roof.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Jarai longhouse, Gialai - Vietnam

inside Jarai longhouse (1997)

Ede longhouse, Daklak - Vietnam

inside Ede longhouse (1994)

2012KojiSato.gif)

In Borneo each ethnic groups build longhouses of their own style and length on the banks of the river because boats are the only transportation available in tropical rainforest. Longhouse, actually corresponding to a village, was relocated or rebuilt every few years or decades owing to shifting cultivation. Besides longhouse there is a men's communal house bori baruk where skulls of enemies used to be stored among Bidayuh people as mentioned above.

Iban longhouse, Sarawak - Malaysia

inside Iban longhouse (1992)

Rungus longhouse, Sabah - Malaysia

inside Rungus longhouse (1993)

There is also so-called longhouse “uma” in Siberut island of the Mentawai islands near Sumatra, where, islanders still live on hunting and gathering, several families of the same clan live together and conduct ceremonies in “uma”.

Siberut longhouse: ceremonial space katengan uma

living space paipai uma (2013)

Apart from genuine longhouse, a row of houses “omo” in south Nias seems to remain unique features of longhouse as its original form. Moreover Gayo house “umah” as well as Batak house “ruma” can be called as a kind of apartment house where multiple families reside together.

row of houses in south Nias (1990)

inside door connect between houses

Gayo house “umah”, Aceh Province (1990)

Batak Simalungun house “ruma”, North Sumatra

2012KojiSato.gif)

Cingkes, Kec. Dolok Silau, Kab. Simalungun, Sumatra Utara (1990)

2. Two Crises of the Cultural Property

Firstly, it should be pointed out that Indonesian architecture is facing destruction of cultural properties as the result of modernization and development of tourism industry, which is happening simultaneously throughout the world; I’m not going further into this in more detail, as you are aware.

Secondly, I will examine a problem that cultural properties often have been destructed and fabricated in the name of "restoration". Restoration should be conducted for the purpose of maintaining its values, but in many cases in Indonesia, restoration deprives of its authenticity. I will introduce some examples.

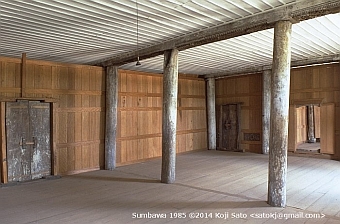

2-1. Istana Dalam Loka, Sumbawa

In Sumbawa, there used to a royal palace called “Dalam Loka” that was built in 1885, which is a continuous form of raised-floor architecture with 99 posts. The palace was restored between 2001 and 2011(?) by receiving technological assistance from Japan, although it was once disassembled and repaired between 1980 and 1985.

Dalam Loka Palace after the 1st restoration

Sumbawa Besar (1985)

Dalam Loka Palace after the 2nd restoration

Sumbawa Besar (2013)

The photograph taken after the first restoration shows that only the posts and doors of the palace are made of old materials, but all other parts have been replaced by new materials. Even though it is barely able to maintain its appearance, we hardly see their advanced carpentry techniques applied at the time of construction.

inside the Palace after the 1st restoration (1985)

same as on the left (1985)

I don't know why Japanese "Agency for Cultural Affairs" targeted this palace for her technical cooperation, however in 2012, the palace had finished restoration with the use of new materials while leaving as many engraved beams as possible. In regard to conservation of cultural properties in Japan, we try to keep the original materials as many as possible, and at the same time, we often make record of traces of restoration in the past and purposefully leave signs of new restoration in order to conserve it close to its original form.

inside the Palace after the 2nd restoration (2013)

same as on the left (2013)

In Japan, there still exist wooden architecture built more than 1000 years ago. For example, Horyuji temple is said to be founded in 607, which had been reconstructed several times over the years. One of its components, Gojunoto (5-story Pagoda), which is acknowledged to be the oldest wooden building existing in the world, there remains only 20% of its original timber as the result of several restorations. Nevertheless, it is still maintaining high authenticity as these restorations had been conducted in order to reflect its original form, which are based on recorded data over the centuries.

In contrast, the original form of the royal palace in Sumbawa no longer exists as it has disappeared through the process of restorations. Even if the palace still hold a good value in tourism, it was already difficult to recognize its old techniques applied and structures during the process of restoration in 1985.

2-2. Ngada, Flores

There is an ethnic group called “Ngada” in the central Flores located in eastern Indonesia. In particular, Bena village can be considered as one of the major tourist village among Ngada, which has been designated for preservation by the state government. The village is a good example to study Ngada culture as it has megalithic monuments including dolmen and menhir that are spread over the village as well as various ritual facilities.

In the centre of a traditional house called “sao”, there is a dark windowless space surrounded by wooden board walls, which is one of the common features of traditional houses in Indonesia, and equipped with a fireplace. Double balcony is installed outside of the entrance, providing a place for daily life.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Bena, Desa Tiwuriwu, Kecamatan Aimere, Kab.Ngada, NTT, Indonesia

Now, let me explain what happened to them after restorations, comparing photos taken in 1986 and 2013. As you see, it is clear that the ridge of the roof has been reconstructed as higher than its original, which requires much more thatching materials of "alang-alang" ([imperata cylindrica]). If unable to procure the materials from surrounding mountains and fields, they have to purchase it from anywhere. Therefore, traditionally the height of roof reflected their economic status and should be kept in a fixed height after all. On the other hand, the higher roof becomes, the more durable because higher roof will prevent rain from leaking and will last long in the end. Then should we accept this kind of modification ?

Bena village, Ngada (1986)

same as on the left (2013)

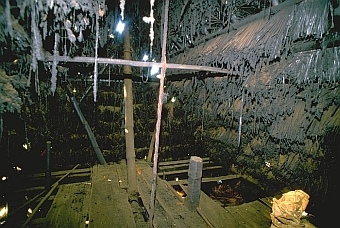

We also need to look at another issue. The attic space of their houses used to have unique atmosphere, which is derived from a method of covering roof using alang-alang.

In general the roof frame for thatching is formed by series of horizontal purlins fixed to the vertically arranged roof rafters, on which thatching materials are bounded. But in Ngada bundles of alang-alang are not bounded to the roof frame but just folded in two against purlins. As a result, back side view of the roof is terribly fuzzy; tips of alang-alang attract soot and dust from hearth, so that we must take a lot of grit to climb up attic for research. In addition, there is a unique method against wind, that is thick ropes of ijuk (black fiber of sugar palm), which connect a ridge pole to a main beam spanned over opposite wall. However, after restration they followed ordinary way of thatching as can be seen in the neighboring island Sumba because the higher roof prevented from using traditional technology. Therefore it seems to be very clean when looking up inside of the present roof.

traditional thatching among Ngada (1986)

present thatching (2013)

It can be suggested that this change in the way of roofing is related to the question of how to evaluate its value as cultural properties. From the standpoint of at least architectural specialist, I would say the unique way of roofing with thatch inherited among Ngada people has disappeared from Indonesia.

2-3. Manggarai, Flores

The next example shows an ethnic group called “Manggarai” living in the western Flores. Manggarai has been well-known for their huge cone-shaped houses called “mbaru” according to records in the Dutch colonial period. However, Manggarai people seemed to be ashamed of such traditional houses as they were outdated. When I had an investigation in 1986, there remained four mbaru only in Waerebo village.

Manggarai house "mbaru" (1986)

inside mbaru (1986)

Maybe it never can be imagined from its appearance, but mbaru is raised-floor houses. A house is divided along circular-shaped external wall into single rooms for 8-10 families, and there is a fireplace in the center of the house placed with stones equal to a number of families. A central main post supporting the roof apex stands at the side of the fireplace, to which a ladder of a thick bamboo accessing to the attic is fixed. Its huge attic space has a three-layered structure, in which harvested cones are stored.

2012KojiSato.gif)

Waerebo, Kec. Satar Mese, Kab. Manggarai, NTT (1986) shown again

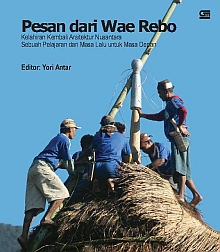

As discussed above is the situation of their houses in 1986. The present aerial photograph explains that the number of houses has increased from four to seven. This was implemented as a part of the policies in Manggarai to conserve their own cultural properties. In fact, restoration of mbaru has been promoted over the several years in cooperation with academic institutions including University of Indonesia; they finally organized an exhibition and published a book to show its process and fruits. I suppose they probably received a prize from UNESCO.

Waerebo village, Manggarai (1986)

Initially, mbaru has been seen as a social unit for exogamy, in which they are engaged in continual wife exchange in these areas. Although it is not certain whether this kind of marriage system still exists after the restoration, it can be said as a successful example that conserved cultural properties while utilizing the development of tourism. The problem is on the side of academia.

There are some reports written about Manggarai culture that give detailed description of their architectural ritual, which makes us not believe our eyes. Why do Waerebo villagers wear sarongs quite formally and put batik clothes like blangkon on their heads when performing rituals? As you may well know, most of them are Christian. When constructing a new traditional house and setting up posts, they should conduct ritual practices by slaughtering pigs and cocks in order to pour their blood under its central post. At least, it was observed in 1986 when I conducted an investigation. However, the report does not contain any photographs of pig sacrifice, whereas it contains those of cock’s. This may be because that their Javanese cooperators did not prefer to slaughter and eat pigs, or otherwise villagers hesitated to do so.

entitled “upacara adat desa Waerebo”

translate “traditional ritual of Waerebo village”

This episode seemingly symbolizes colonisation of local cultures by Java that is happening throughout Indonesia, rather than being discussed within the academic framework.

For instance, in Manggarai, there is another village called Todo in which a royal family used to live. Their traditional cone-shaped houses, nine “mbaru niang” (drum house) were there, had already been lost in 1986 when I visited the village. Fortunately with the support of a foundation in Switzerland one of mbaru niang was reconstructed in 1992 - this house still can be seen today. When I visited again in 2013, I was requested to wear sarong in order to enter the house although this never happened before the restoration in Waerebo village.

As is often the case new traditions are invented by tourism, nevertheless it is disappointing to say that they are not very much concerned about the history of their houses. In recent years, it seems that they have tended to promote it for commercial use without paying any respect to their ancestral properties.

"Pesan dari Wae Rebo - kelahiran kembali arsitektur Nusantara : sebuah pelajaran dari masa lalu untuk masa depan" (Message from Wae Rebo - rebirth the architecture of Nusantara : a lesson from the past to the future), 2010

2-4. Candi Prambanan

Finally, I will introduce an example that is a bit different from the previous examples. Candi Prambanan is decorated with wall relief describing various architectural forms in Indonesia, which provides us a rich resource for study of architectural history.

relief of Candi Wisnu “King Ugrasena is enthroned again as the King of Mathura”

Candi Prambanan (1985)

Let me just quickly explain about features of houses depicted on the reliefs.

- Its boat-shaped gable roof is inclined outward, which is often considered to be a historical indicator of boat symbolism.

- Different from reliefs appeared in the later period, the roof has no decoration so that means it is probably thatched.

- The house is raised-floor, and there is a veranda called “selambi” installed at one side of the main structure.

- Its structure is characterized by stone foundation that is placed under the post; diagonal braces support floor beams with posts; horizontal tie beams penetrate through posts to reinforce the the whole construction.

Thus it can be understood that they already had advanced and sophisticated techniques to be applied to wooden architecture. Similar images can be seen on the other reliefs of Candi Borobudur and Candi Prambanan having almost same features; one can assume that these images are representation of Javanese houses in the 7th-9th centuries.

Candi Borobudur 8-9c

Candi Prambanan 9-10c

According to a general understanding of history of Indonesia, they transferred the capital from central Java to eastern Java in the later period. In eastern Java, a number of candis have been built and its reliefs are completely different; many of the subjects include hipped roof and pyramid roof whereas boat-shaped gable roof can be found on the relief in Candi Prambanan. Scale-like pattern are depicted on the roof, which represents tiles or shingles. By comparison with Candi Prambanan, the raised-floor has been placed at a lower level, which has a veranda-shaped structure in which sitting human figures are drawn. Posts are placed on the foundation stone, whole of which is built on the stone platform.

Candi Jago 13-14c

So far we have looked at some example of candis and its reliefs in order to introduce the general overview of the history of wooden architecture in Indonesia.

I would like to add another interesting example; that is reliefs in Selomangleng Cave located in the suburb of Kediri city. This cave is said to have been built between 10th and 11th centuries, when they transferred their political centre from central Java to eastern Java. Interesting building depicted on the relief have specific features of both periods, high raised-floor, and diagonal braces which supports the floor that disappeared in the later period. The roof remains in a boat-shaped form, but at the same time, scale-like pattern can be also found.

relief of Selomangleng Cave

Selomangleng Cave, Kediri c.10-11c (1985)

History is filled with mysteries. One of the reliefs in Candi Prambanan describes a roof that has patterns of tile-shaped curves, which cannot be found in either Candi Prambanan or Candi Borobudur. Does it imply that tiles have been used prior to those periods?

×Candi Brahma, Candi Prambanan

○Candi Brahma, Candi Prambanan

If looking it carefully, the line patterns are roughly drawn. There is no doubt that it is a mischief made by someone in the later period, which carpenters maybe aware of when conducting restoration. Needless to say, such restoration work must be operated under strict management, although it is probably not possible to manage it in detail in reality. However, we should not overlook such mischief, otherwise the history of Indonesia will be converted into different directions; I hope that the existing history are not doubtful.

Epilogue

My first investigation research in Indonesia was conducted in a small island of the Moluccas chain. As it is common for any Indonesian traditional society, they also had a customary law called "adat" to inherit their cultural tradition from generation to generation. According to "adat", customary councils were established to manage social events and to impose penalties for offenders. In addition, the village chief was handed over political power from central government aside from adat; that means there existed two different power structures in a small island. Moreover this village chief also served as pastor (priest), therefore in position of having both political and religious powers to control the society. In contrast, customary councils tried to take control of the village by applying a traditional religion what they called "Hindu", which is a kind of animism and adat as well.

These two forces always generated conflicts at every opportunity. For example, if I conduct investigation in the village, I should firstly contact with the chief by showing written permission from the central government, but customary councils would not allow me to conduct research on traditional houses. This kind of problems often happened when I was in the village.

Regarding modernization of the island, we tend to consider that the chief hope to carry out modernization and development, whereas customary councils hope to keep their tradition. The story is not easy at all. The chief wanted to gain financial resources by promoting tourism therefore he would rather preserve traditional houses as tourism resources. But, customary councils were willing to change thatched roof into corrugated iron roof and to build foundation of raised-floor house filled with concrete because they believed it would strengthen the durability of adat tradition. Moreover, if any houses or buildings are constructed on the premise that practicing ritual and providing adequate spatial constitution based on adat philosophy, then they can be considered to be "adat house".

This kind of political situation over traditional houses must be happening across the whole extent of Indonesia. We have to re-consider how we categorize "traditional houses" and "cultural properties" and determine its authenticity. Moreover, it is necessary for us to ask ourselves; what kind of influence does preserving and utilizing cultural properties have/bring about on the local community?

I am participating in a project to preserve traditional settlements in Nias island located west of Sumatra. Particularly, Bawömataluo village is a large settlement of more than 100 of traditional houses. When visiting this village for the first time, I was surprised by huge traffic of people because in many cases most young people move from traditional villages to suburbs whereas old people remain in village. But in the village in Nias island, people are flooded, and they are able to make a daily life in comfort. You will see kids are playing everywhere. This is unusual in other most traditional settlements.

Bawömataluo village, South Nias (2011)

Onohondrö village, South Nias (2012)

Excepting Nias island, traditional houses still remain as settlement unit in some areas in Indonesia such as Toraja in Sulawesi island and Sumba island. People in Toraja still continue to construct a traditional ancestral house called "tongkonan". They are also known with their grand-scale funeral, and they tend to build higher and more valiant tongkonan as long as they can in order to show their richness. The present tongkonan is considered to be the symbol of power of clan rather than dwelling. One of the most magnificent tongkonan used to exist in Nanggala village was rebuilt as a completely new house in 2005. As long as they maintain their tradition, they will continue replacing old tongkonan into new one with more and more curved and upswept roof.

Nanggala village, Tana Toraja (1991)

same as on the left (2005)

On the one hand, because inside of traditional tongkonan is dimly lit and have poor ventilation, it has brought about harsh environment for children. This has resulted changes adapting modern life. Fireplace is removed with kitchen to outside that enables to avoid smoke-fillings in inside of house. They install day lighting window on the wall, widen entrance (that was originally narrow), make high-walled space.

Sa'dan village, Tana Toraja (2005)

Ketekesu village, Tana Toraja (2005)

The fundamental issue facing people in Toraja is that young people are not willing to live in traditional house. In these days, we do not see many people in a traditional settlement of Toraja. If there is still tongkonan in the village, in many cases, people are moving into modern dwelling called “banua”, which has been constructed behind tongkonan.

So, why are the people in Nias still willing to live in traditional houses? -its answer for the question is that they are suitable for contemporary life by providing confortable living space.

Bawömataluo village, South Nias (1990)

Bawömataluo village, South Nias (2011)

In general, traditional houses in Indonesia do not equipped with windows.

In Sumba island, ancestral spirit called “marapu” is placed inside the highpeak hipped roof of their houses. When conducting activities including construction of houses, they perform ritual ceremony for marapu, and they go on to next step after checking the response from marapu. The people seem to be living in a part of "marapu’s house" by paying their respect to marapu. To this extent, houses may not exist for human life; it rather exists for their ancestors to bring together by providing closed space in darkness.

inside "marapu’s house", West Sumba (1987)

ritual for marapu, East Sumba (2009)

Considering from an aspect of conservation, it is unexpectedly easy to conserve uninhabited houses like tongkonan in Toraja, but is not in the case of Nias because the traditional houses still serves as living space for them. In fact, in Nias island, renovation work on their traditional houses including kitchen and bathing area have been often carried out corresponding to modern living.

thatching a roof in Wunga village, East Sumba (2009)

スンバ | Sumba

スンバ | Sumba

スンバ島で家屋を建てる (Build a Sumbanese house)

スンバ島で家屋を建てる (Build a Sumbanese house)My discussion goes back to the first question, “what is the purpose to preserve cultural properties?” Conserving cultural properties should be treated as conserving culture. If conservation activity of cultural properties result in the displacement of young people in the settlement, it will be difficult to inherit and maintain their cultural traditions even if the traditional houses are newly rebuilt.

It can be suggested that accepting their natural and real lifestyle as such, for instance, the laundry is spreaded all over the pavement, becomes one of the themes of cultural tourism. Only visiting uninhabited villages or museums may not be informative enough to comprehend the present situations around them; we therefore need to explore new more directions to conserve cultural properties. (2015-08-30)

Bawömataluo village, South Nias (2012)

Library Digital Archives of the “Architectural Institute of Japan” (AIJ)

Library Digital Archives of the “Architectural Institute of Japan” (AIJ)

- 建築雑誌編集部 「大東亜建築グラフ(フィリッピン篇)」『建築雑誌』56-689, pp.1-16, 1942

- 建築雑誌編集部 「大東亜建築グラフ(マレー、スマトラ、ジャワ、バリ篇)」『建築雑誌』56-690, pp.17-52, 1942

- 建築雑誌編集部 「大東亜建築グラフ(3)」『建築雑誌』57-694, pp.53-76, 1943

- SARGEANT, G. T. & Saleh, R. “TRADITIONAL BUILDINGS OF INDONESIA Vol.1: BATAK TOBA”, Direktorat Penyelidikan Masalah Bangunan - U.N.Regional Housing Centre, Bandung, 41P, 1973

- SARGEANT, G. T. & Saleh, R. “TRADITIONAL BUILDINGS OF INDONESIA Vol.2: BATAK KARO”, Direktorat Penyelidikan Masalah Bangunan - U.N.Regional Housing Centre, Bandung, 48P, 1973

- SARGEANT, G. T. & Saleh, R. “TRADITIONAL BUILDINGS OF INDONESIA Vol.3: BATAK SIMALUNGUN AND BATAK MANDAILING”, Direktorat Penyelidikan Masalah Bangunan - U.N.Regional Housing Centre, Bandung, 51P, 1973

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari “KOMPENDIUM: SEJARAH ARSITEKTUR Jilid 1”, Yayasan Lembaga Penyelidikan Masalah Bangunan, Bandung, 217p, 1978

- SARGEANT, P. M. “Traditional Houses in Indonesia: Traditional Sundanese Badui-Area, Banten, West Java”, Masalah Bangunan 18-1, pp.14-19, 1973

- SARGEANT, G. T. “Traditional Houses in Indonesia: Batak Karo -- North Sumatra”, Masalah Bangunan 18-3, pp.2-4, 1973

- SARGEANT, G. T. “Traditional Houses in Indonesia: Batak Simalungun and Batak Mandailing -- North Sumatra”, Masalah Bangunan 18-4, pp.10-15, 1973

- SARGEANT, P. M. “Traditional Houses in Indonesia: Timor (Atoni) Nusa Tenggara”, Masalah Bangunan 18-4, pp.16-27, 1973

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: Central Java” 1 & 2, Masalah Bangunan 19-2, pp.32-38; 19-3, pp.23-28, 1974

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: East Java”, Masalah Bangunan 19-4, pp.31-38, 1974

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari (ed.) “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: Minangkabau -- West Sumatra,Masalah Bangunan” 20-1, pp.26-35, 1975

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari (ed.) “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: Palembang -- South Sumatra” 1 & 2, Masalah Bangunan 20-3, pp.31-34; 20-4, pp.23-30, 1975

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari (ed.) “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: the House of Lampung and Bengkulu in Southern Sumatra” 1 & 2, Masalah Bangunan 21-2, pp.40-42; 21-3, pp.23-27, 1976

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari (ed.) “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: Bengkulu -- South Sumatra”, Masalah Bangunan 21-4, pp.34-37, 1976

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari (ed.) “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: the Dayak Long-House Community”, Masalah Bangunan 22-1, pp.37-39; 22-2, pp.42-44, 1977

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari (ed.) “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: the Last "Lamins" of the Dayaks”, Masalah Bangunan 23-1, pp.33-40, 1978

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: Jakarta, Preserves Its Rural Part”, Masalah Bangunan 23-2, pp.24-34, 1978

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: Poso-Toraja”, Masalah Bangunan 23-3/4, pp.45-50, 1978

- SUMINTARDJA, Djauhari “Traditional Housing in Indonesia: the House in Tana Toraja”, Masalah Bangunan 24-1, pp.38-40; 24-2, pp.35-36, 1979

- MELALATOA, M. J. “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH ISTIMEWA ACEH”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 142P, 1984

- SITANGGANG, Hilderia (eds.) “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH SUMATERA UTARA”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 194P, 1986

- “Arsitektur tradisional Daerah Sumatera Barat”

- ABU, Rifai (ed.) “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH RIAU”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, P, 1984

- ABU, Rifai (ed.) “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH JAMBI”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 143P, 1986

- SIREGAR, H. R. Johny & ABU, Rifai “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH BENGKULU”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, P, 1985

- ABU, Rifai (ed.) “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH LAMPUNG”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 125P, 1986

- “Arsitektur Tradisional daerah Sumatera Selatan”

- DAKUNG, Sugiarto & ABU, Rifai “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH KALIMANTAN BARAT”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, P, 1986

- DARNYS, Raf & ABU, Rifai “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH KALIMANTAN TENGAH”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 78P, 1986

- DARWIS, Raf & ABU, Rifai “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH KALIMANTAN SELATAN”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 156P, 1986

- “Arsitektur tradisional daerah Kalimantan Timur”

- “Arsitektur Tradisional Daerah Sulawesi Utara”

- SYAMSIDAR BA (eds.) “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH SULAWESI TENGAH”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 163P, 1986

- MARDANAS, Izarwisma & ABU, Rifai & MARIA “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH SULAWESI SELATAN”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, P, 1985

- MARDANAS, Izarwisma “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH SULAWESI TENGGARA”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 181P, 1986

- ABU, Rifai (ed.) “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH JAWA BARAT”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 140P, 1983

- REKSODIHARDJO, Soegeng et al. “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH JAWA TENGAH”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 242P, 1984

- DAKUNG, Sugiarto “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 264P, 1983

- GELEBET, I Nyoman “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH BALI”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 476P, 1985

- MUHIDIN, Lalu Ahmad “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH NUSA TENGGARA BARAT”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 106P, 1986

- ABU, Rifai (ed.) “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH NUSA TENGGARA TIMUR”, Bagian Proyek Inventarisasi dan Pembinaan Nilai-Nilai Budaya Nusa Tenggara Barat, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Mataram, 219P, 1991

- PUDJA, Arinton I.G.N. & ABU, Rifai “ARSITEKTUR TRADISIONAL DAERAH IRIAN JAYA”, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Daerah, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta, 86P, 1986

- CUNNINGHAM, Clark E. “Order in the Atoni House”, Bijdragen tot de Taal-,Land- en Volkenkunde 120, pp.34-68, 1964

- NEEDHAM, Rodney (ed.) “RIGHT AND LEFT: ESSAYS ON DUAL SYMBOLIC CLASSIFICATION”, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 449P, 1973

- FOX, James J. (ed.) “THE FLOW OF LIFE: ESSAYS ON EASTERN INDONESIA”, Harvard Studies in Cultural Anthropology 2, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 372P, 1980

- DOMENIG, Gaudenz “TEKTONIK IM PRIMITIVEN DACHBAU: MATERIALIEN UND REKONSTRUKTIONEN ZUM PHANOMEN DER AUSKRAGENDEN GIEBEL AN ALTEN DACHFORMEN OSTASIENS, SUDOSTASIENS UND OZEANIENS: EIN ARCHITEKTURTHEORETISCHER UND BAUETHNOLOGISCHER VERSUCH”, Organisationssstelle für Architekturausstellungen ETH Zürich, 197P, 1980

- DUMARCAY, Jacques (tr. by Michael SMITHIES) “THE HOUSE IN SOUTH-EAST ASIA”, Images of Asia, Oxford University Press, Singapore, 74P, 1987 《ジャック・デュマルセ『東南アジアの住まい』(佐藤浩司訳),学芸出版社, 111P, 1987》

- WATERSON, Roxana “THE LIVING HOUSE: AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF ARCHITECTURE IN SOUTH-EAST ASIA”, Oxford University Press, Singapore, 263P, 1990 《ロクサーナ・ウォータソン『生きている住まい:東南アジア建築人類学』(布野修司監訳), 学芸出版社, 303P, 1997》

- BELLWOOD, Peter S. “MAN'S CONQUEST OF THE PACIFIC: THE PREHISTORY OF SOUTHEAST ASIA AND OCEANIA”, Oxford University Press, 1979

With regard to the platform-house of Pingpu people Li Yih-Yuan pointed out the relationship to that of Micronesia and Polynesia.

- 李亦園 「臺灣南部平埔族平臺屋的比較研究」『中央研究院民族學研究所集刊』第3期, pp.117-144, 1957 (LI, Yih-Yuan “On the platform-house found among some Pingpu tribes in Formosa”, 1957)

- 千々岩助太郎 『台湾高砂族の住家』丸善, 1960 (CHIJIWA, Suketaro “HOUSES OF TAIWANESE ABORIGINES”, 1960)

- photo by TORII, Ryuzo 142-7226 “Scene from Paiwan village” 1896-90 ~ 「東京大学総合研究資料館標本資料報告」18, 1990

Promotive Association of Torii Ryuzo Archives

Promotive Association of Torii Ryuzo Archives

- LINTON, Ralph “The Material Culture Of The Marquesas Islands”, Memoirs of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum 8-5, pp.271-297, 1923

- CHRISTIAN, F. W. “EASTERN PACIFIC LANDS ; TAHITI AND THE MARQUESAS ISLANDS”, Robert Scott, London, 1910

- FROBENIUS, Herman “Oceanische Bautypen”, Zeitschrift für Bauwesen 49 with Atlas, pp.553-580 and pl.57-59, 1899

- KUBARY, J. S. “ETHNOGRAPHISCHE BEITRÄGE ZUR KENNTNIS DES KAROLINEN ARCHIPELS” 3vols, P.W.M.Trap, Leiden, 1895

- “Scientific American Supplement” 26 August 1899, with the caption: “A native hut on Yap Island, showing stone money leaning against the right wall.”

microbuds

microbuds

- SATO, Koji “Menghuni Lumbung: Beberapa Pertimbangan mengenai Asal-Usul Konstruksi Rumah Panggung di Kepulauan Pasifik”, Antropologi Indonesia 49, pp.31-47, Jurusan Antropologi FISIP Universitas Indonesia, 1991

TO DWELL IN THE GRANARY

TO DWELL IN THE GRANARY

- 乾尚彦 「棲み方の生態学 1- 隠された高床:フィリピン・北部ルソン島ボントック族の住居」『住宅建築』91, pp.93-104, 1982 (INUI, Naohiko “Hidden Raised-Floor: Houses of Bontoc people in northern Luzon”, 1982)

- Riedel, J. G. F. “DE SLUIK- EN KROESHARIGE RASSEN TUSSCHEN SELEBES EN PAPUA”, 1886

- SCHÄRER, Hans “DIE GOTTESIDEE DER NGADJU DAJAK IN SÜD-BORNEO”, E.J.Brill, Leiden, 1946

- VROKLAGE, B. A. G. “Das Schiff in den Megalithkulturen Sudostasiens und der Sudsee”, Anthropos 31, pp.712-757, 1936

- LEWCOCK, R. & BRANS, G. “The Boat as an Architectural Symbol”, in P.OLIVER (ed.) SHELTER,SIGN & SYMBOL, pp.107-116, The Overlook Press, Woodstock-New York, 1975

- HEINE=GELDERN, Robert “The Drum Named Makalamau”, India Antiqua, pp.167-179, 1947

- 石毛直道 「文化人類学の眼⑭ ニューギニア高地の住居」『都市住宅』6911, 1969 (ISHIGE, Naomichi “Houses in New Guinea Highlands”, 1969)

- 石毛直道 『住居空間の人類学』SD選書 54, 284P, 鹿島出版会, 1971 (ISHIGE, Naomichi “ANTHROPOLOGY OF HOUSE SPACE”, 1971)

- SVOBODA, W. “Die Bewohner des Nikobaren-Archipels”, International Archiv fur Ethnographie 5, pp.185-195, 1892

- Elio Modigliani “L' isola delle donne : viaggio ad Engano”, 1894

- GRUBAUER, Albert “CELEBES: ETHNOLOGISCHE STREIFZÜGE IN SÜDOST- UND ZENTRAL-CELEBES”, Hagen, 152P, 1923 《グルーバウエル『セレベス民俗誌』清野謙次訳, 小山書店, 1944》

- 伊能嘉矩 「DYAKのHEAD-HOUSEと台湾土蕃の公廨」『東京人類学会雑誌』21-246, pp.455-459, 1906 (INOU, Kanori “Head-house of Dayak people and Communal house of Taiwanese aborigines”, 1906)

- Photograph by INOU, Kanori “Youth Warrior House takuvan of Puyuma people”, 1907

- SCHERMAN, L. “Wohnhaustypen in Birma und Assam”, Archiv fur Anthropologie 14, pp.203-235, 1915

- HOFFET, J. H. “Les Mois de la Chaine Annamitique Entre Tourane et les Boloven”, Terre Air Mer la Geographie 59-1, pp.1-43, 1933

- WEHRLI, Hans J. “BEITRAG ZUR ETHNOLOGIE DER CHINGPAW (KACHIN)”, 83P, E.J.Brill, Leiden-Zurich, 1904

- Photograph by John THOMSON “Old Pe-po-hoan women, Lan-long, Formosa”, 1871

Wellcome Library

Wellcome Library